In Mangalore, we had contacted someone running a Mangalore tiles factory. They were kind enough to give us a tour of the production facility. During the tour, we learned that the pioneers of the Mangalore tiles were the German Basel Missionaries, a Christian missionary society that settled in Mangalore around the mid-19th century. The Basel Missionaries discovered the rich alluvial soils along the banks of Gurpur and Netravati rivers and started the first factory in 1865, on the banks of Netravati river near Jeppoo under the management of a certain Geoge Plebst. Coincidentally, we ended up staying right next to this factory, and the Netravati river.

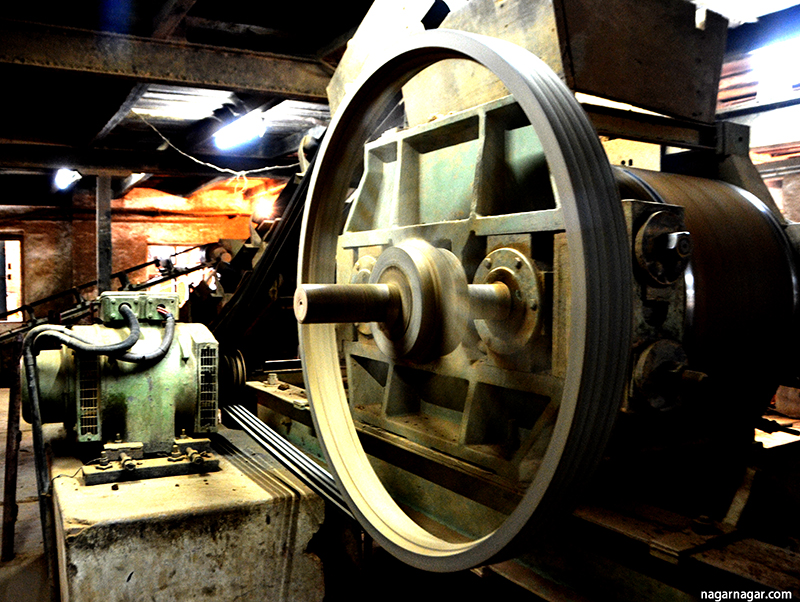

The process of seeing clay transform from the mud lying in the backyard of the factory grounds in its most natural, unassuming, non-technical and rawest form turning into beautiful burnt red tiles was incredible. The process of production is a mix of labour and relatively simple machines including preparation of the clay by its mixing, grinding; cutting the clay it into tile slabs of required sizes (pugging); pressing/moulding of the slabs into the tile presses; putting the stamp/seal of the manufacturer; and at various other points along the assembly line/conveyor belts. Once made, they are first dried naturally and then put into baking ovens where they harden to their usable threshold. The various categories of finished tiles are based on parameters such as strength, usage, ornamentation and so on.

Though the industry once provided an economical and reliable roofing material and was flourishing till few decades back, it is now facing a steep decline in terms of its demand. In the factory that we visited, some of the machines were not functioning because of lack of labour and lack of demand. There used to be almost 50 tile factories in the region but now only a few remain in operation. The industry had built itself upon the natural advantages of the region which included great quality of clay, firewood, labour and suitable weather.

Several times we passed the black and white board reading The Commonwealth Tile Factory-Manufactures of Basel Mission Tiles, bearing the mark of the manufacturers Commonwealth Trust Limited (CTL). The board was peeling off with only a few characters making themselves visible to spell out what they meant. This surviving board, bearing the name of the factory that bore the entire Mangalore tile industry, felt symbolic of the strong and dogged fight the tiles are upto against the various alternate building and roofing materials. Thus it was only justified and, an event of immense happiness for both of us, when we found ourselves under a terrace tiled with CTL tiles (as well as tiles of the factory we visited), when we were hosted by the generous friends Neha and Shail in Bangalore.