Rameswaram was our southern most point for this trip. We were both extremely excited at the prospect of seeing the ocean again. Both of us have an unsaid competition on who would be the first person to spot the ocean. On our drive to Rameswaram, we were both caught unsuspectingly when suddenly the ocean just appeared next to us (on right side first and then left) beyond the seemingly abandoned buildings less than 50 meters away from the road.

Just as we were getting used to the idea that we had the ocean next to us on two sides, we came upon the Pamban Bridge - connects Pamban Island (on which Rameswaram lies) to the Indian mainland. Pamban Island has a number of small fishing hamlets along with Rameswaram town. The ocean on both sides has is vast with hues of blue, the bridge running parallel to the railway bridge which is running much lower, closer to the ocean.

As we drove through the small town of Rameswaram, the town was filled with lodges teeming with pilgrims. It had the small buildings typically seen in villages and other than the yellow autos plying the streets it seemed like an overgrown village. In our attempt to get to our hotel, we got stuck in a narrow alley more than once, sometimes these alleys were also barricaded. Forcing us to reverse through the narrow alleys. We also passed by the site where the late Honourable President APJ Abdul Kalam was recently laid and we paid our homages.

Our stay at Rameswaram was memorable but two experiences were truly outstanding. The first was the full darshan experience at the Ramanatha Swami temple and the second was the drive and the overwhelming feeling of being at the end of land, at Dhanushkodi, tip of the Palk Strait, where one can feel that the next land mass is a different country.

We arrived in Rameswaram in the afternoon and were planning to spend the afternoon just walking around an acquainting ourselves with the city. After a homely meal in one of the small messes, we spoke to a local who suggested that we do the darshan that day itself since the next day would be extremely crowded. There is an specific way to see the Ramanatha Swami temple, which includes bathing in the sea followed by being bathed (pouring a bucket of water) from 22 tirthas (wells) and they drying yourself, changing into a clean set of clothes before appearing before the Shiva Linga at the center of the temple. We found a guide that helped us through the process and proceeded to take a dip in the Bay of Bengal at Agniteertha.

The whole experience of running between wells with different waters (varying both in temperature and as Tarun says taste as well) was surreal. Along with a diverse community of people varying in ages, regions, gender, undergoing the same experience as us, the walk of the wells felt a unifying experience, neutralising a lot of differences. After changing, we progressed to the do the darshan which in itself was powerful. However, the experience and adrenalin rush from the 22 wells was something else.

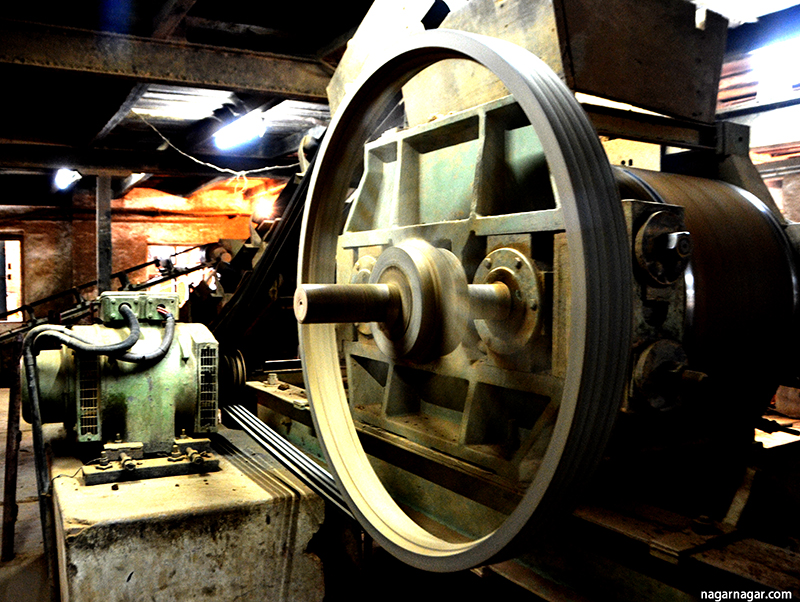

The drive to Dhanushkodi was another overwhelming experience. It was once a bustling border and port town, now reduced to a ghost town, since it got washed away in a 1964 cyclone . The town used to have a train station, post office, customs office, schools and a busy market. However, after the cyclone, the town was never rebuilt and was deemed unfit for living by the government. Now, one can see some of the relics of these buildings. The stones of the track ballast were still visible along what would have been the railway track, though the iron track itself is gone. Access to the town as well as the lands end on the Indian mainland going into the Palk Strait is along the ocean and sometimes even through the ocean. Currently only accessible using the permitted 4 wheel drive jeeps and vans but a road is under construction and should open in the next 6 months or so.

We were not sure if we will be able to get to the point where we are surrounded by water on three sides, with the Bay of Bengal on one side and the Indian Ocean on the other. When the driver did take us there, both of us were taken by the breathtaking view. It was surreal to be at this point that we had heard so much about. It would also be the closest either of us had ever been to Sri Lanka. What was especially intriguing was that the Indian Ocean had waves that rose at least 2 to 3 feet smashing into the beach and just 20 feet on the other side, the Bay of Bengal lay still and calm. It was surreal, unbelievable almost.